Trust is the fabric of any prosperous society. It’s what makes voluntary cooperation flourish and enables trade and human progress.

But trust is an extremely local phenomenon. We have been hardwired over millennia to trust—and maintain stable relationships with—only a small number of people, typically around 150, according to Dunbar’s number. It’s likely you have transacted and exchanged value with countless more people than that throughout your lifetime.

How, then, can we depend consistently and safely on those we consider strangers? More to the point: What is the best way to extend trust beyond our immediate circles in a globalized, digital world where exchanges span vast networks? How does trust work in global finance? These questions are even more relevant in the context of the developing world, where financial innovation has historically lagged.

For answers, we must first look to the insights of people like economist Hernando de Soto, computer scientists Miller and Stiegler, and—most importantly—legendary cypherpunk Nick Szabo.

The Limitations of Traditional Trust Models

The main idea all these thinkers converge on is that trust scales very poorly, becoming a bottleneck for economic growth. In fact, it scales so poorly that there is little chance that the small 'trust networks' illustrated below will ever have the opportunity to connect with each other. Throughout history, this limitation ensured most of humanity remained stagnant and poor.

Figures like de Soto and Szabo have devoted themselves to exploring mechanisms by which societies have attempted to overcome these barriers. Central to their discussions is the role of institutions or “trust hubs”—legal systems, financial markets, and governmental bodies—as intermediaries that extend trust by standardizing interactions across larger groups, enabling cooperation to scale.

There are, of course, other factors at play.

Culture, for example, also plays a critical role in shaping and scaling trust within societies. High-trust societies benefit from cohesive cultures, which is helpful because it embeds norms and rules within our behavior without requiring many laws. As Deutsch explains, institutional, as well as cultural and genetic knowledge (thanks to natural selection), undergoes a constant process of error correction, similar to scientific knowledge, which evolves over many years.

Over the centuries, institutions such as the judiciary and banking have undergone significant transformation—and, at times, radical overhaul—reflecting the dynamic nature of cultural evolution. These changes have been most pronounced in countries more historically open to self-critique and adaptation. Today, we refer to these countries collectively as "The West,” and the unprecedented rate of progress observed within them since the Enlightenment is by no means coincidental.

It’s worth noting, however, that even within these countries, institutions remain deeply localized and require significant human effort to function, often limiting their global applicability and scale.

The Digital Evolution of Trust

The digital age has shifted focus among thinkers like Szabo towards exploring how we can facilitate global cooperation among strangers through the use of computer networks and innovations like blockchains and smart contracts. These innovations not only streamline transactions but also allow for the creation of digital markets in which trust and contract enforcement are automated, significantly reducing the need for cumbersome legal frameworks and extensive bureaucratic oversight.

While reaching consensus on rights, obligations and who owns what requires an extremely expensive legal apparatus, blockchains hold the promise of automating that consensus, just as Bitcoin does with digital private property.

Such advances raise compelling questions about the potential to build entirely new systems of trust—systems that are not only more inclusive but also more efficient than those that have dominated the past. It is no exaggeration to say these digital innovations could be key to unlocking a new era of global economic interaction and cooperation.

The Impact of Digitalization on Traditional Structures

Digital tools allow us to drive change at unprecedented speed, enabling the creation of new institutions in traditionally isolated jurisdictions, for example, free from practically all of the aforementioned limitations. Such institutions can build credibility and deliver services at scale, reaching global markets at dramatically low cost.

We are seeing similarly dramatic change in the West, with established institutions under scrutiny like never before. Mostly that is because the internet allows us to access and analyze information on a scale which, just a few decades ago, would have been unfathomable.

Of course, we now also have alternatives that offer far greater transparency, efficiency, and accountability. These alternatives are most vividly apparent in areas such as the media and universities, where social networks and online education have significantly transformed the way we access and disseminate information.

But there’s also another area that’s witnessed equally dramatic change, which forms the core of my research: financial institutions.

Redefining Trust with Blockchain Technology

Consider stablecoins, perhaps the most impactful blockchain application to date. These digital versions of fiat currencies exemplify how blockchain can extend the reach of established first world financial institutions like the Federal Reserve. By digitizing the US dollar, a global distribution channel has effectively been created, accessible to anyone with an internet connection - and it's growing fast.

Blockchain networks offer unique features that streamline the verification and management of all kinds of digital assets beyond stablecoins. They serve as systems for tracking these digital assets—or, as Szabo called them, property titles—on a secure, immutable ledger.

This capability ensures that participants can trust the system's integrity without the need for mutual trust among users. It fundamentally alters how trust is brokered globally, extending the reach of reliable transactions beyond traditional geographic and institutional boundaries.

Blockchains in a Nutshell

The main goal of a blockchain is to agree on the truthfulness of its shared ledger in a way that minimizes the need for trust. By making the information natively digital, we decrease dependency on external elements and trusted third parties (TTPs). This radical reduction in trust requirements mitigates the necessity for heavy regulation and the creation of new, potentially fallible institutions, which would put us squarely back where we started.

Here, we return to the insights of Nick Szabo, who famously wrote that blockchain governance generally comes in only three varieties:

1) Lord of the Flies, where the blockchain is dominated by a single leader, failing to achieve consensus and centralizing control

2) Lawyers, in which the system is bogged down by regulation and intermediaries, stifling scalability and flexibility

3) Ruthlessly trust-minimized, as is the case only with Bitcoin, which turns lawyers into hash calculations via proof-of-work.

Szabo, perhaps unsurprisingly, favored the “ruthlessly trust-minimized” approach. When asked, “Why ruthlessly?” Szabo responded: “Otherwise the children or the lawyers will win.”

Szabo’s observation is indeed poignant: without ruthlessly minimizing trust, we default to ineffective systems dominated either by autocratic control or cumbersome legalities. His metaphor underscores the importance of designing systems that are both efficient, as well as resistant to the pitfalls of over-regulation and centralization.

This approach to blockchain governance is vital because it addresses a core issue: traditional trust mechanisms simply do not scale well in a globalized digital world. By integrating blockchain technology—and Bitcoin’s “ruthlessly minimized trust” specifically—into our digital infrastructure, we can create more robust, scalable, and inclusive systems. These systems are not just theoretical, either—they are operational now, growing rapidly as they connect users across the globe with reliable services at low cost.

Why Bitcoin is the Key to Scaling Global Trust

Bitcoin is distinguished for being the first—and only—successful attempt to implement the ideas of Szabo et al. when it comes to scaling global trust in the digital era. Unlike with traditional financial markets, where the goal is to establish a consensus on the truthfulness of transactions, Bitcoin introduces a fundamental requirement for censorship resistance. This attribute is vital because the value of the Bitcoin token hinges on its ability to be owned and transferred irrespective of any legal constraints. In essence, for a digital means of exchange to truly be neutral and globally accessible, it must be resistant to legal interventions from any particular set of countries—either it is resistant to all, or it is resistant to none.

This necessity for censorship resistance creates a self-reinforcing cycle where Bitcoin's stakeholders prioritize maintaining its value by avoiding any changes to the code that could compromise its foundational properties. As a result, Bitcoiners show little interest in modifications that might increase transaction rates or block sizes, focusing instead on preserving the security and integrity of the system.

This is why Bitcoin can be viewed as private wealth or property that exists independently of traditional legal frameworks—a revolutionary concept in the realm of finance.

The Historical Context of Self-Custodied Wealth

There are other qualities inherent to Bitcoin that would doubtless be familiar to our ancestors. The idea of self-custodied wealth, for example, is far from a modern invention. It has been a fundamental apect of human societies for millennia. Historically, protecting one's assets required either the threat or use of violence. Bitcoin transforms this dynamic by enabling the ownership of valuable assets without the need for physical force, either by the individual or by the state.

This shift is crucial because if Bitcoin were susceptible to legal manipulations, its credibility as a reliable store of value could be undermined overnight. Bitcoin’s ability to operate beyond the reach of capricious legal systems makes it an ideal tool for fostering global cooperation among parties who may not necessarily trust one another.

Avoiding new regulations, excessive legal interventions, and the complications of traditional governance structures with Bitcoin and similar technologies offers a promising avenue for decentralized cooperation without the historical necessity for trust.

A Multi-Chain World?

While Bitcoin pioneered decentralization and established a robust model for a trustless system, numerous other blockchain projects have followed, each issuing its own token and claiming similar levels of decentralization. Simply issuing a token, however, does not achieve true decentralization—and this is what so many people building their own chains severely misunderstand. True decentralization, as exemplified by Bitcoin, is crucial for avoiding single points of failure, ensuring that the network remains robust against various forms of attack or legal interference.

Within the Bitcoin ecosystem, miners, developers, and users have aligned incentives to maintain the network's integrity and maximize the token's value. This alignment is achieved because Bitcoin’s value is inherently linked to its decentralized nature.

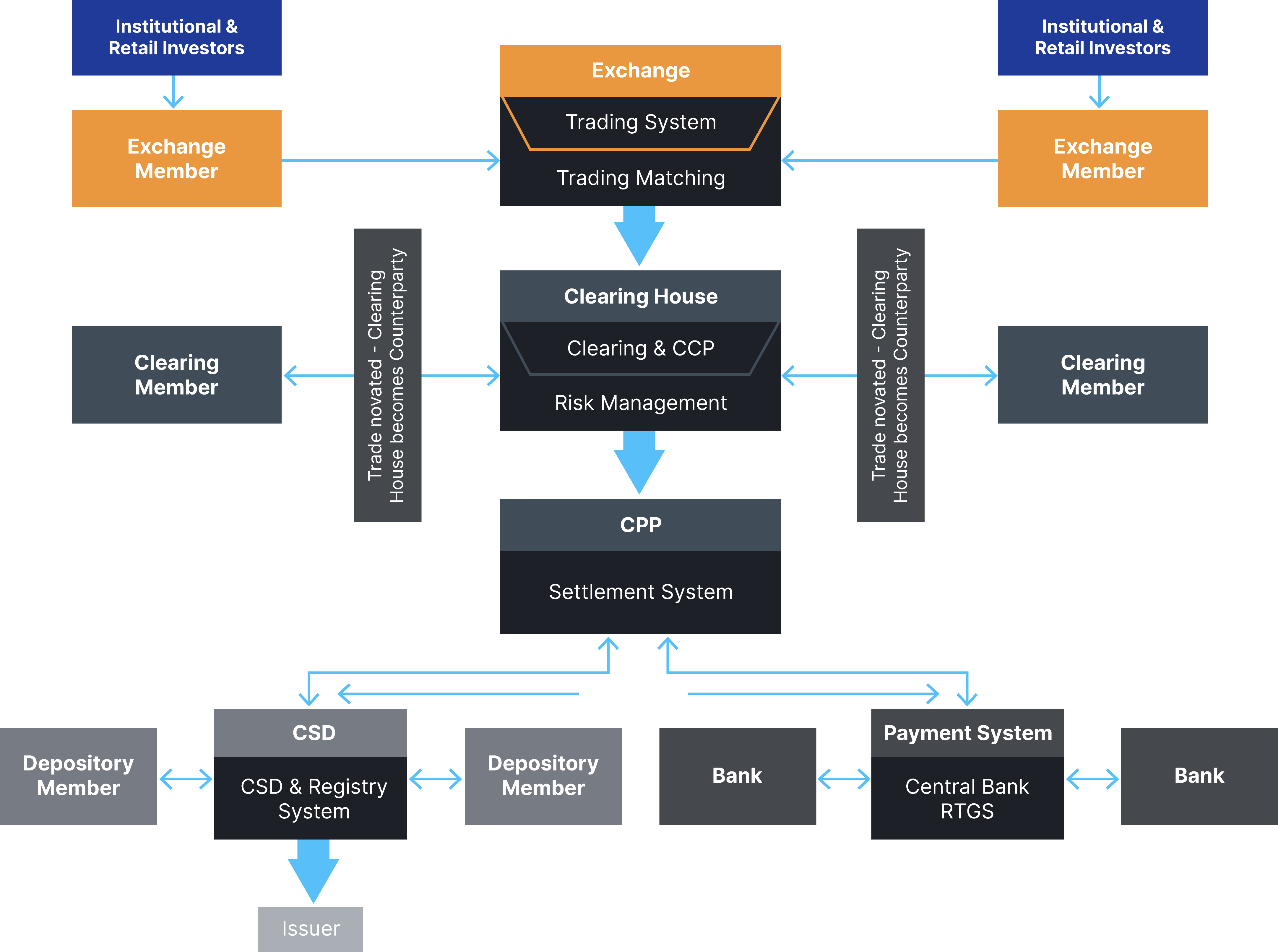

On the other hand, the shared incentive for those seeking to use a blockchain for financial applications is to ensure that the shared ledger remains truthful. This paves the way for functionalities that make advanced financial systems possible being built on top.

This is exactly how things work in traditional finance, where national stock exchanges, clearing houses and even central banks operate as federations of members that vote in order to agree on how to keep the ledger truthful.

We can do all of this with code, with members voting to create software rules a majority agree on.

However, when a native token is added to the mix, it introduces a conflict of interest between the desire for a decentralized ledger and the drive to maximize token value, resulting in misaligned incentives.

In the long run, such systems tend to break… or result in a software fork.

Nevertheless, that has not stopped the emergence of a slew of blockchain projects that prioritize high transaction volumes and sophisticated smart contract functionality in an effort to attract financial institutions - and invariably enrich the projects’ founders. But anyone with a minimum understanding of distributed systems will tell you that when you aim for such rich functionality and true decentralization on the same chain, you achieve neither.

That’s why a number of banks have been experimenting with private consortiums which, while fully controlled and less prone to volatility, lack the transparency and finality of public blockchains.

The Liquid Network: Balancing Decentralization with the Needs of Modern Finance

One initiative that’s been particularly successful in reconciling the trade-offs inherent to blockchains between sufficient decentralization and attending to the demands of modern finance is the Liquid Network.

Pegged 1:1 with Bitcoin itself, negating the need for a native token, this Bitcoin sidechain enhances Bitcoin’s core functionality with features like faster, confidential transactions and the ability to issue digital assets ranging from stablecoins to securities such as bonds, equity or promissory notes.

While Liquid offers these enhancements, it operates under a federated model rather than the fully decentralized model of Bitcoin itself. The trade-off in decentralization is a necessary compromise to accommodate the advanced features and performance demands that are not feasible on Bitcoin’s base layer due to its stringent consensus mechanisms.

All of this makes Liquid especially attractive to businesses and financial institutions requiring the robust security of Bitcoin with the added benefits of high-speed transactions, enhanced privacy and the ability to adhere to regulatory standards.

Empowering the Global South with the Liquid Network

The potential of Liquid extends into impactful real-world applications, as illustrated in the case of Mexican digital signature pioneer, Mifiel.

As Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto highlights in his book "The Mystery of Capital," so-called “poor” countries are not actually poor at all—they are home to literally trillions of dollars in untapped wealth in the form of non-liquid assets. The challenge lies not in the absence of wealth but in the lack of sophisticated systems to turn these assets into capital that can drive economic growth.

Leveraging Liquid, Mifiel has been able to address these challenges head-on in the context of tokenized promissory notes. Despite being the most commonly-used debt instruments in Mexico, paper-based promissory notes have traditionally suffered significant issues in terms of scalability and security. Efforts to digitize them certainly represented an improvement, but did not solve the core problem of verifying and tracking ownership due to the lack of a reliable central registry.

Liquid provided a solution in the form of the necessary infrastructure to issue these notes securely and transparently. Since its implementation in January 2023, the initiative has seen substantial success, issuing over $1 billion in digital notes. These blockchain-based notes have enabled local non-banking financial institutions in Mexico to access global liquidity, using these securely tokenized assets as collateral.

This breakthrough demonstrates how Bitcoin, specifically through so-called ‘layer-2’ technologies like Liquid, can revolutionize financial systems. The most dramatic effects will undoubtedly be seen in developing countries, where Liquid can provide a robust mechanism for transforming local assets into globally recognized capital. Mifiel’s success not only underscores the viability of this technology in complex financial ecosystems but also highlights its role in enhancing economic stability and growth in regions traditionally hindered by inefficient financial services.

Winners and Losers

As innovations such as Liquid demonstrate Bitcoin’s significant potential to reshape global finance, it is crucial to consider the broader regulatory and market environments in which these technologies operate. The differing impacts of blockchain technology in various jurisdictions highlight a clear divide in potential winners and losers, shaped by the regulatory frameworks they operate within.

Think of it this way: the more laws and regulations required to participate in financial markets, the less benefits will be derived from a blockchain and vice versa. Conversely, the greatest benefits are reaped in environments where regulatory burdens are minimized, allowing for the full potential of blockchain's efficiency and transparency to shine.

This scenario underscores why the perception of blockchain in developed markets as merely “just another commodity” is fundamentally flawed. For blockchain to revolutionize financial systems, it must operate in a framework that avoids the pitfalls of legacy regulatory infrastructures that can encumber its capabilities.

This means also avoiding networks plagued by buggy smart contracts, Miner Extractable Value (MEV), vulnerability to hacks, front-running risks, or misaligned incentives that prioritize token value over technological performance, attracting the hammer of regulation.

Ideally, blockchain systems should feature natively on-chain, trust-minimized means of exchange that maintain neutrality and avoid fungibility issues, reducing the need for traditional third-party oversight. If jurisdictions ignore these aspects and continue to rely on burdensome regulations, they risk merely replacing old supervisory mechanisms with new ones, failing to address underlying inefficiencies.

Jurisdictions focused on minimizing trust and enhancing security are likely to thrive and attract innovative use cases, as with Mifiel’s issuance of promissory notes on the Liquid Network.

Ironically, the jurisdictions likely to benefit most from these innovations are the very developing countries which, until now, have found themselves largely on the sidelines of the global financial system. Free from the complex regulatory frameworks and entrenched legacy systems that often impede innovation in The West, these countries have the unique opportunity to circumvent traditional barriers to entry, leapfrogging their more developed peers.

The Promise of Bitcoin Architecture

As we continue to confront global challenges of economic disparity and unequal financial access, Bitcoin’s architecture is especially promising, given its ability to facilitate trust in the digital age precisely by removing the need for it. This technology extends far beyond being just another method of payment, offering a framework for a more equitable and inclusive global financial system.

Trust can only scale in developing countries if we minimize the need for it (like laws or regulations), and the only way to achieve that is by replacing that need for security paranoid and trust-minimized protocols. By turning those laws (wet code) into software (dry code), we remove the human component that has required such an intense error correction process over decades or even centuries in the West.

Removing those decades enables developing countries to be able to create fully functional financial systems leaner and more efficient than those in the West.

Consider this: you cannot substitute the need for laws and regulations with an insecure blockchain, one that carries the risk of MEV, frequent hacks, buggy smart contracts, or lacks confidentiality to prevent investor front running. If that were the case, regulators would have to establish new rules and laws to manage the aftermath of these issues. This would essentially bring us back to square one, creating more of the same problems we are aiming to solve.

Embracing A Multigenerational Opportunity for the Developing World

Laws are necessary because human behavior is often unpredictable and undesirable, making coexistence challenging without some minimum rules. In an ideal world where everyone behaved predictably, laws would be unnecessary. The same logic applies to blockchains in financial markets.

In financial systems with blockchains plagued by bugs, hacks, and manipulation, laws are needed to regulate and address failures and disputes—a luxury many countries cannot afford due to weak regulatory and enforcement mechanisms. A truly secure, trust-minimized blockchain can replace laws, lawyers, and trusted institutions with software, thereby automating consensus. This is revolutionary for those in countries distrustful of their governments or where the rule of law is weak or non-existent as it provides a secure way to hold assets without relying on offshore jurisdictions.

Ultimately, blockchains can only be viewed as commodities in regions with strong regulatory and enforcement apparatuses, like the EU or USA, where they offer limited problem-solving benefits. In contrast, in fragmented markets and developing countries, blockchains like Bitcoin and Liquid can significantly enhance financial systems by providing a reliable, decentralized means of establishing trust and property rights.

As we enter a new era powered by Bitcoin, those who have historically been left behind could very well lead the charge in scaling trust not just locally but on a truly global scale. In doing so, they would be transforming from their status as outsiders into outstanding examples for us all on how to build fairer and more inclusive financial systems.